If you spend any time in the shady woods that surround your homestead, chances are you have run into patches of Solomon’s seal from time to time.

This handsome plant looks like it belongs in your garden as much as it does beneath a thick canopy of trees, so it is no surprise that it is starting to show up in people’s shade and woodland gardens these days.

However, beyond its beauty, Solomon’s Seal is edible as well. Here is everything you need to know about foraging for Solomon’s seal, or growing it on your homestead.

History and Origins

Solomon’s seal is a perennial plant that shares genes with a wide variety of other plants. Solomon’s seal has been noted in history as an edible plant, although it is not often a top plant foragers search for.

This shade loving woodland denizen is often confused for its familiar and similar twin plant, False Solomon’s seal. The distinction between the two plants is important to learn before searching for and foraging Solomon’s seal.

The real Solomon’s seal plant is known by its scientific name, Polygonatum biflorum, and its alternative name, King Solomon’s Seal. Solomon’s seal is part of the Asparagacea family, and the Nolinoideae subfamily.

The Nolinoideae subfamily formerly was called and known as the Ruscaceae family, which may be important to know if an outdated plant identification book. Solomon’s seal was also formerly a part of the Liliaceae family, due to its similarities with Lily of the Valley flowers.

The genus name, Polygonatum, originates from ancient Greece, which translates to “many knees”. This name choice refers to Solomon’s seal’s multiple jointed rhizome.

The name Polygonatum is the genus name, which is the primary family Solomon’s seal belongs to. The secondary half of the scientific name, biflorum, refers to the specific species the plant is in the family.

Since there are many varieties of plants within the Polygonatum family, it is recommended to learn the names of plants you wish to forage for easier identification.

Identification

Solomon’s seal is native to North America, with many of its sibling plants being natives to other countries across the globe. The Solomon’s seal in North America, commonly found in the United States, can be mistaken for a type of lily based on its white flowers.

This perennial plant grows back every year, resulting in clumps that can be transplanted, and can be collected to be grown domestically.

Solomon’s seal reaches a height of up to one to two feet tall, maturing in the early spring and summer months between April and June.

Depending on the variety, other varieties of Solomon’s seal, particularly the fragrant versions, can grow to be up to seven feet tall. The leaves, flowers, and berries are key characteristics of identifying Polygonatum biflorum apart from other varieties of Solomon’s seal.

The leaves are oval, or egg- shaped, that have subtle veining on the top side. The leaves grow in a zig-zag pattern on the arching stem. The stem provides the height of the plant by growing tall then arching out and over. In the autumn season, the leaves turn a golden yellow or brown color.

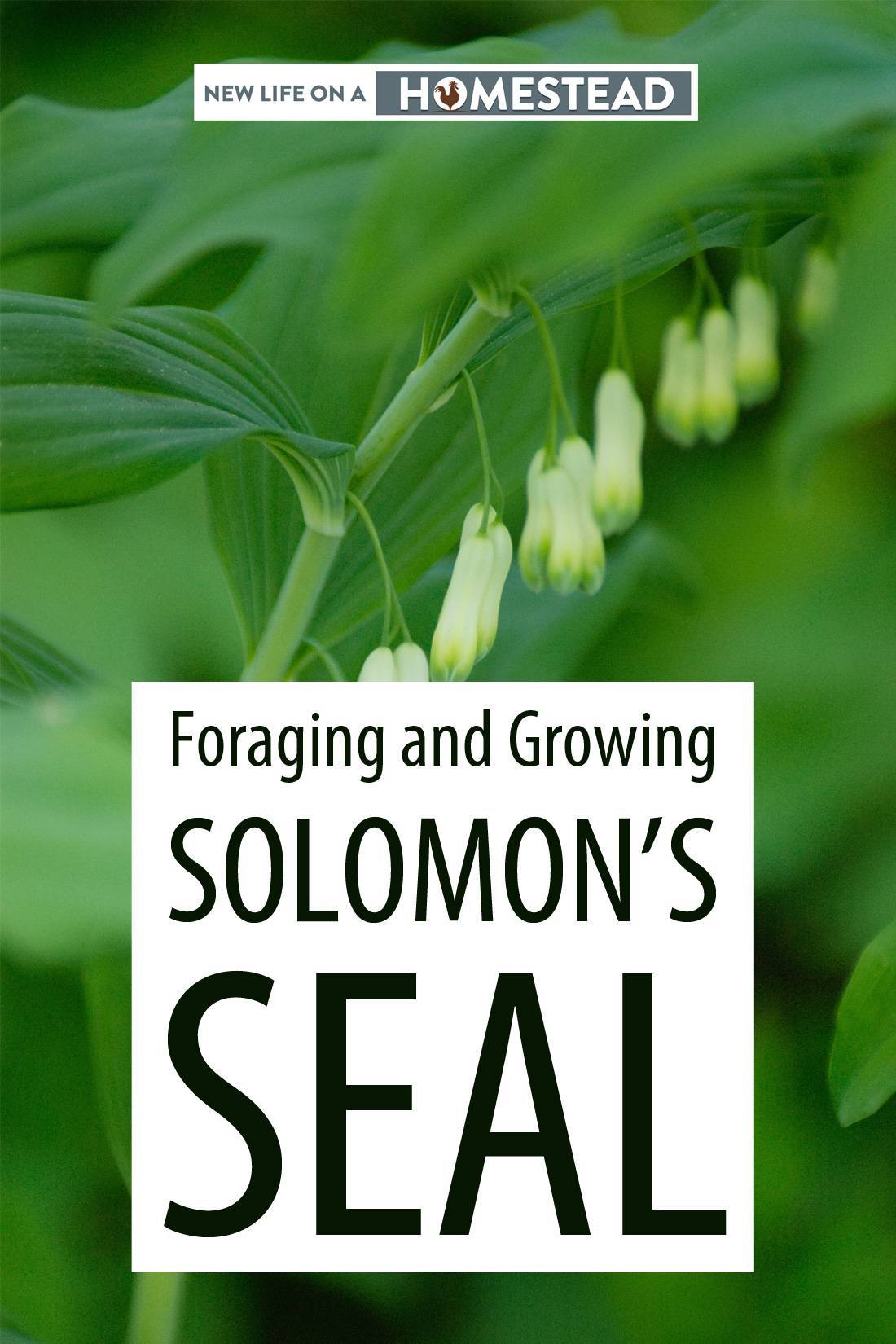

Underneath the leaves and stems, flowers will grow. Solomon’s seal flowers differ from other popular varieties, as they are slightly bell shaped.

These flowers will most often bloom in yellow or white with green tips, and in clusters of two to ten blooms per cluster. From the flowers, berries will grow in their place.

Solomon’s seal berries look similar to blueberries, as they appear a bluish-black shade, but are smaller and firmer. The berries will begin to grow in the months of May and June.

The rhizomes, or the roots, have a thickness of around one inch to one and one fourth inch. The rhizome of the real Solomon’s seal is white after it is properly cleaned of soil.

Once they are harvested, the rhizomes of well-established plants will have indents or “scars” from previous growth cycles. The scars will be rounded or resemble the shape of two inverted triangles.

The triangular scars may be responsible for the plant’s name, as the inverted triangles are similar to the King Solomon’s royal seal. From the rhizome, the arched stems will grow, one stem per rhizome.

Similar Plants

The Solomon’s seal plant shares characteristics with over 70 different plants in its species, in addition to being most often confused as a variety of lily or for its unrelated look alike, False Solomon’s Seal. Popular alternate forms of Solomon’s seal include Polygonatum odoratum and Polygonatum “prince charming”.

Polygonatum odoratum is set apart from the biflorum variety by the white color found on the edges of the leaves and is similar to the other varieties with its gentle scent of lilies. Polygonatum prince charming is a variety that blooms earlier than other varieties and only reaches about one foot in height.

False Solomon’s seal is the most common look alike of true Solomon’s seal, so much that it even shares a similar name. This plant is the reason for the necessary precautions before harvesting and consuming plants that look similar to Solomon’s seal.

When using a plant identification book, False Solomon’s seal will be categorized under an entirely different botanical name, known as Maianthemum racemosum.

Identification between these two plants can be quite difficult when it is not during their flowering stage, and information from online sources can send mix signals because of this. False Solomon’s Seal varies slightly in appearance compared to true Solomon’s seal, if you compare the leaves, flowers, and berries.

False Solomon’s Seal leaves are similar in shape, but have a slight wave pattern around the edges. The flowers grow in a different place on the plant, as well, growing on the ends of the stems, rather than underneath.

False Solomon’s Seal flowers grow in larger clusters, of 20 to 80 blooms per cluster, and grow in a star-shape, rather than true Solomon’s Seal’s bell shape. This false version of the Solomon’s seal plant also grows in riskier conditions, such as rockier and drier soil conditions.

Another plant to keep an eye out for during your identification process is the False Solomon’s Seal’s close cousin, the Starry False Solomon’s Seal, known by its scientific name, Smilacina stellata. The Starry False Solomon’s Seal grows incredibly similarly to both False and true Solomon’s seal, including reddish brown berries that grow in the place of the white flowers.

How to Forage and Use Solomon’s Seal

The Solomon’s seal plant grows in colonies, developing more as the plant matures. The largest colonies are often found across the country, but are most commonly found in the mountains, sandhills, and coastal plains.

Before setting out in search of true Solomon’s seal, it is recommended to keep two plant identification books on your person. This is to avoid accidental misidentification, which can be taken a step further when identification is taken to credible online sources after the harvest is complete.

Additionally, as noted earlier, Solomon’s Seal is easily found in nurseries these days, as it is primarily sold as a foliage plant; if you plan to establish a colony of these plants on your homestead, it may make sense to simply stop by your garden store to see if they have any in stock (see gardening tips below).

In the early spring, you can harvest the shoots of this plant; remove the leaves from the shorts and then prepare them just like you would asparagus. Make sure you have previously identified the plant as being Solomon seal prior to harvesting the shoots, since they look different than a mature plant.

The plant’s rhizomes, or roots, are also edible, and are easiest to dig up during the spring. Digging up the rhizome is as simple as digging straight down alongside the base of the plant and pulling it up.

Here is a great video that discusses harvesting Solomon’s seal rhizomes:

Be prepared and know exactly what your plans are for the rhizome, as the root needs to be used or transplanted immediately, or it will need treatment. Solomon’s seal roots will quickly go into dormancy, which will make the root ineligible for planting.

If you do not plant to use or transplant the rhizome immediately, then when the rhizome lays dormant, you will need to process the root through a process called stratification.

If you plan to consume the rhizome, simply wash and clean it and then it is ready for use. While the rhizome is not particularly tasty, it can be added to stews to give a meal more variety and texture.

Growing Solomon’s Seal

Solomon’s seal thrives best in zones three to nine in North America, in places such as mountains, sandhills, or coastal plains. There are multiple species that thrive in their own native conditions across the globe as well. The key identifiable parts to Solomon’s seal are the berries and flowers that grow in the spring and summer months.

When foraging, it is best to wait until the flowering stages of the Solomon’s seal plant, to be able to make an accurate identification. Making an absolute certain identification is crucial to keeping you and anyone else who would be using or consuming this plant safe and out of harm from toxins.

Solomon’s seal grows best in partial shade, in damp and cool soil. This plant should receive at least two hours of consistent sunlight each day, and up to six hours of sunlight maximum. Solomon’s seal is slightly drought resistant, but grows best in well drained, moist soil. When watering, do not overeater this plant, as this can lead to root rot.

Solomon’s seal also benefits more from slightly acidic soil. If you have a garden or yard that is not nutrient sufficient for Solomon’s seal, this is easily remedied by adding a layer of compost to the Solomon’s seal each year.

Compost will provide organic matter that will maintain the pH levels, while also maintaining moisture and a cool temperature.

As the Solomon’s seal plant runs through each growth cycle, leave the leaves as they decay and fall to the ground. The dead leaves will act as natural mulch and compost, keeping the plant nourished, cool, and moist.

The easiest way to grow Solomon’s seal is from fresh clippings of the root. From root to a full mature plant, here are important steps in each stage:

Beginning Stages

The most common, and perhaps easiest, way of starting a Solomon’s seal plant is from transplanting an existing plant or by planting a rhizome. It is possible to start growing your own Solomon’s seal through seed propagation, but this route can be difficult.

The best time to collect rhizomes or seeds for propagation is in the spring and fall, when the plant is dormant for the year. The younger the plant, then more regularly it should be watered to maintain moist soil.

The Solomon’s seal plant is popular for its voluminous foliage and texture, meaning that this plant would be best planted in areas that allow for plenty of growth.

Starting with freshly collected rhizomes, Solomon’s seal can take up to two years to sprout and reach full maturity. If the rhizome if fresh and has not laid dormant, then plant the root directly into slightly acidic soil.

Soil that ranges between pH level six and pH level eight are good levels to work with. Plant the rhizome in an area that receives plenty of shade and that has cool soil. Keeping the soil cool can be achieved by laying a layer of mulch and compost each year.

It is important to keep the rhizomes moist in the initial stages of their growth. Young plants should be watered regularly, but not to the point of excessive sogginess.

If your rhizome has reached the point of dormancy, then it can remain in dormancy for up to a year and will need to be revived before then before being planted.

To pull your dormant rhizome back into a state that is ready-to-plant, you will need to provide a cold treatment to the seeds or rhizome. This treatment is called cold stratification and is done by keeping the seeds or clipped root cold and moist at a consistent temperature of 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Maintenance

Solomon’s seal is a relatively low maintenance plant, once it is established in secure and nutrient dense soil.

Growing from the rhizome can prove to involve more maintenance, due to how long it takes to prepare and grow Solomon’s seal from scratch, often taking over two years before it reaches full maturity for planting. With a fully mature plant, however, even the fully grown Solomon’s seal plant does not need deadheading.

While this plant does not require consistent transplanting every year, if you are interested in increasing the number of Solomon’s seal plants, then the best option is to divide your current, most mature plant.

Divide the plant at the rhizomes, then transplant approximately 18 inches apart. Other plants that pair well with Solomon’s seal are bleeding hearts and different varieties of ferns, hostas, and Liguria, since each of these plants have similar growing conditions, mainly the partial shade requirement.

How to Deter Pests and Disease

Solomon’s seal is not a common target of well-known pests and diseases of gardens. However, when Solomon’s seal does encounter such issues, the most common culprits are fungal disease or slugs and snails.

Solomon’s Seal can catch a fungal disease due to being overly watered, as the extra water will puddle around the plant roots, creating additional moisture. It can be considered a deer-resistant plant, as it is not favored by deer to eat, so it would teach deer to steer clear of other nearby plants.

Although Solomon’s seal is slightly drought resistant, it does not fare well against strong winds, as the thin, long flower stems are easily broken. This is easily remedied by being mindful as to where you plant Solomon’s seal. If possible, plant behind a guarded area, behind a tree or fence for example, to keep the plant from experiencing breakage.

The Solomon’s Seal plant is a great attractor for birds and butterflies, as a result of the plant’s flowers and berries.

Although this plant does no experience great amounts of pests or disease, it is recommended to have an alternative deterrent on hand as a preventive measure. In case of either of these issues occurring, there are a variety of remedies available.

For snails and slugs, there are a variety of natural substances that deter these pests, including:

- Coffee: fresh coffee grounds contain caffeine, a natural stimulant that deters and can kill pests, and have an unpleasant texture that snails and slugs do not like.

- Beer: Flat beer and the scent of the flat drink deters pests. Bury a safe container in the soil, leaving just the rim above ground, nearby the plant and pour the flat beer into the container.

- Egg shells: The texture of broken up eggshells deters snails and slugs since the rough edges will harm the soft flesh of pests. Egg shells also provide a source of calcium to plants.

For fungal disease, the best options include minor maintenance and hydrogen peroxide. Fungal diseases can infect every part of Solomon’s seal, and one of the easiest ways to keep fungal disease at bay is to clip the infected foliage off.

Each time a piece needs to be clipped away, cut leaves and flowers away at their stems, then burn or dispose of the clippings away from the plant. A hydrogen peroxide spray can help keep the disease at bay, with one part peroxide to nine parts water. Spray liberally after clipping infected foliage.

Safety Precautions

There is little to noncurrent evidence to defend the use of Solomon’s seal for any medical purpose. There have been a few studies conducted on Solomon’s seal and the plant’s interaction with the body.

Such studies show that Solomon’s seal can have an impact on blood sugar levels by decreasing them. This is important to know if you are, or know someone who uses insulin, takes medication for low blood sugar or is diabetic.

Solomon’s seal negatively interacts with medication used by diabetics, increasing the likelihood of blood sugar levels dropping to dangerously low ranges. Any part of the plant that is not the rhizome should not be consumed, as the other parts are toxic, especially the berries.

Parting Thoughts: A Useful and Handsome Shade Perennial

Solomon’s seal makes a great addition to any garden, with its understated beauty, hardiness, and propensity to slowly spread as it establishes itself.

It is also a useful woodland plant to forest for food as well. So, learn all you can about this plan, and prepare to plant or forage for it as soon as you can!

When Tom Harkins is not busy doing emergency repairs to his 200 year-old New England home, he tries to send all of his time gardening, home brewing, foraging, and taking care of his ever-growing flock of chickens, turkey and geese.

Hi Tom, thanks so much, this is rich with useful info!

The photo at the end of the article is helpful… can you post more photos for identification and differentiation from false solomon’s seal.

The photo at the beginning is not solomon’s seal, it is some type of blueberry or huckleberry, something in the ericaceae family. Just for the editor’s info.